Why You Liked … LitRPG Before It Was Cool

Think LitRPG started with Ready Player One? Think again.

Long before you could grind levels in a LitRPG novel, Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame showed us what it meant to truly play the game. Modern LitRPGs let you exploit the system, but these classics forced you to survive it.

This is Part 1 of a 3-part series on LitRPG: its roots, how to write it, and why it keeps us hooked.

Before LitRPG was a genre, books like Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame set the foundations for game-inspired storytelling. This is where it all began—long before stat sheets took over.

Next up: How to Write LitRPG Without Losing the Plot, where we get into crafting compelling LitRPG that doesn’t drown in spreadsheets:

The finale: Overthinking: Is LitRPG Just Escapism, or Something Deeper? – where we get deep and metaphysical on why this genre is so damn addictive:

Introduction

LitRPG (short for Literary Role-Playing Game) is what happens when storytelling hooks up with game mechanics and produces a deeply nerdy lovechild. At its core, it’s about characters progressing through a structured game-like system, often complete with XP, stats, and level-ups. While it’s taken off faster than a rogue on a caffeine bender in recent years, its roots go back long before Kindle Unlimited turned it into a book factory for the stat-obsessed.

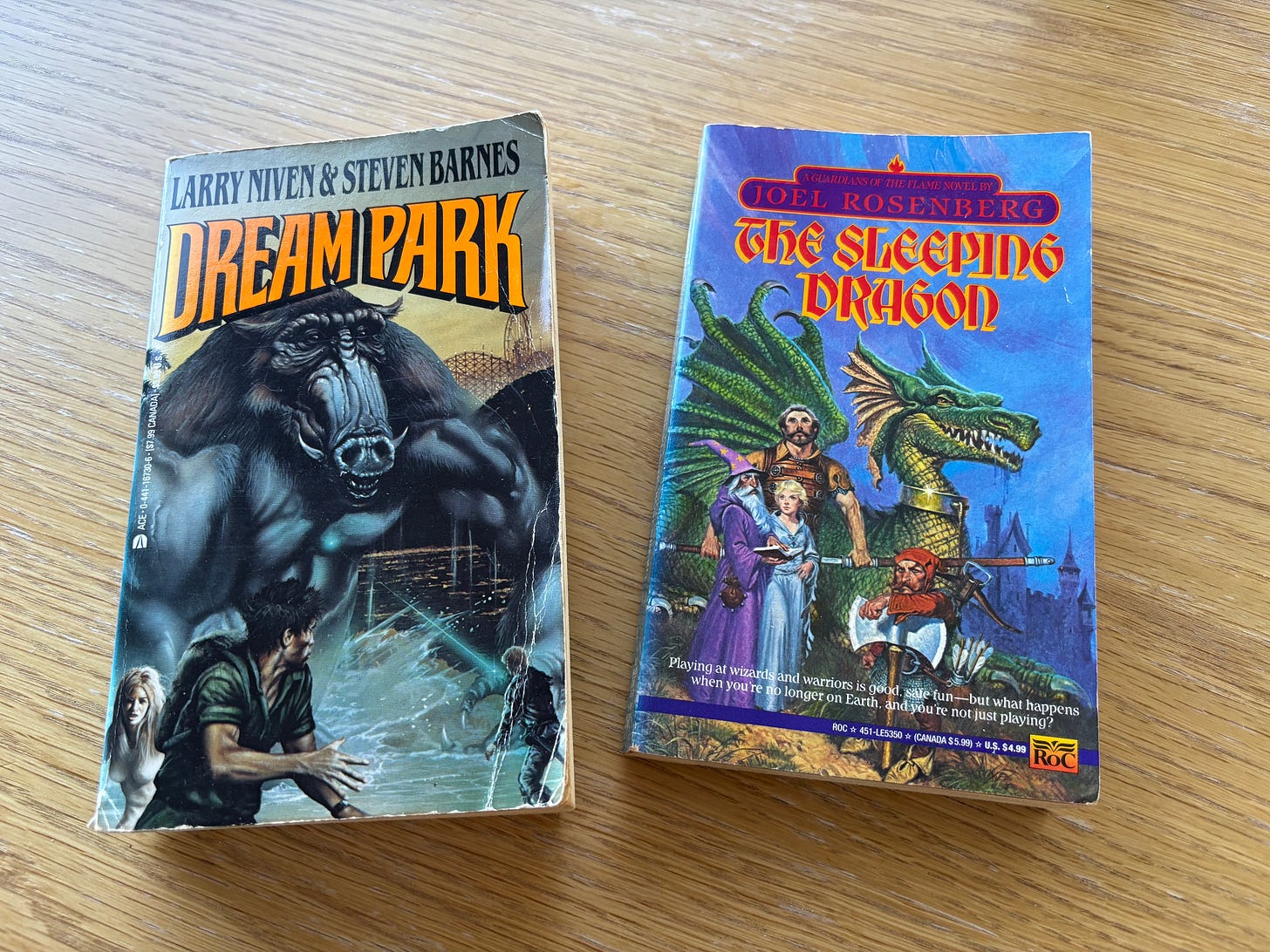

Before Ready Player One gamified geek nostalgia for a broad audience, books like Dream Park by Larry Niven and Steven Barnes and Joel Rosenberg’s Guardians of the Flame series laid the groundwork for what LitRPG could be, before anyone called it that. These early books defined LitRPG back when it was still finding its feet, and before it became a competitive sport in min-maxing. Instead of treating worldbuilding like a side quest, they made adventure, lore, and actual stakes the main event. Failure meant something more than just an inconvenient respawn.

This might sound mechanics-heavy, but there’s a trick these stories use to get everyone closer to genre fiction. You ever notice how urban fantasy is an easy entry point for readers? Whether it’s Twilight’s sparkly vampires or The Dresden Files’ grimy magic, the real world part is already built. You fucking live there, dude. The author just tweaks a few things, and suddenly, you’re chasing vampires through Manhattan.

LitRPG pulls the same trick. Instead of making readers learn an entire fictional world from scratch, it uses gaming mechanics they already know. Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame submerge their stories in familiar systems, making immersion effortless. It’s why LitRPG draws such a broad audience, including readers who might never touch traditional fantasy or sci-fi.

Technical shit aside, Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame ask a very simple question. What if playing a game wasn’t escapism, but became your reality?

I can tell you, as a teenager reading this, my body was ready to explore that calculus. And I think every LitRPG and fantasy fan will be there as well, because these books still hold up for modern readers, in many ways better than the genre they helped form.

Dream Park: a sci-fi fantasy LARP before we knew WTF that word salad meant

“Dream Park” is both a series and the name of the first novel. In the late 21st century, role-playing games evolved beyond dice rolling into theme park extravaganzas, completely immersive for players to experience their wildest fantasies in. You’re no longer Alex Griffon the chief of security; you’re Griffon, the thief espionage specialist who can pick locks with a thought, a prayer, and half a hairpin.

Dream Park’s conceit is the use of holograms, sensory programming, and theme park physical spaces to engage in real-time, high-stakes scenarios. Actors play NPCs. Game masters create elaborate scenarios the players run through. They pay for a ticket, but these are pinnacle events backed by the International Fantasy Games Society; only the best get to play at the theme park, and merchandising and movie rights will sweep up all available cash far better than Disney’s managing with Star Wars or Marvel today. It’s big bucks, but those high-tech toys that make it real are where the mystery of this novel kicks in. Within the first few pages, someone gets unceremoniously deleted from existence, flipping the RPG session into a full-blown mystery-thriller.

If you peeled back all the tech and genre-fiction tropes, Dream Park would be a superb thriller. It’s got believable heroes, motivated villains, chumps in the wrong place at the wrong time, and all the characters are acting to the clockwork laid down by Niven and Barnes.

Dream Park’s game mechanics don’t overwhelm the story, they enhance it. This isn’t spreadsheet fiction. The characters rely on wits and teamwork, not character sheets. The authors knew audiences of the time were more mainstream fiction or sci-fi, and no fool was going to pay attention to something that sounded like Dungeons & Dragons. The game world is immersive, but the novel is more immersive—it does a prestige so profound you don’t even notice it until after the credits roll. See, while the game world is McMassive, the players (our heroes) must still rely on their wits and teamwork. Because there’s a real murderer in the group, stats don’t count for shit, and this is the principal hook that pulls mainstream readers in.

And because it’s a thriller wrapped inside a game, the book isn’t just an adventure. It’s a cerebral smackdown. The murder subplot doesn’t just keep the players guessing; it drags the readers along for the ride, making them question what’s part of the game and what’s an actual corpse. It’s a whodunnit of masterful proportions, with clues so well-hidden you’ll feel like a genius when you spot them. Or, a complete Muppet when you don’t.

Finally, it really feels like a tabletop RPG come to life. Dream Park captures the dynamics of actual RPG groups, minus the Dorito fingers and locker-room smell. It’s this critical focus on character and agency that makes the story pop off the pages and live rent-free in your mind for years. And, I’d say, many later wondered if they could take the concept and turn it into its own genre: LitRPG.

Content Warning: Hazards May Fall from Above

While the debut Dream Park novel is epic, where you sit on the sequels will be mixed. I’d recommend treating it as a one-and-done, but if you get into the books hard, for all that’s holy pull up before you get to the fourth book, the Moon Maze Game. Even the title screams, “Do Not Touch,” like a frog that’s way too brightly coloured to be safe.

The first three books mostly follow Dream Park’s head of security, Alex Griffon, and circle around repeat characters like Acacia Garcia, who pulls double duty as a sometime love interest. The fourth book jettisons Alex like last week’s trash, introducing us to a cast of asshats and fuckheads we just don’t care about. It really crawls up its own ass by setting the whole thing on the Moon, forgetting what made Dream Park great: it’s the characters, stupid, not the faux sci-fi.

Since we’ve mentioned Acacia, we should also touch on a critical fumble of many sci-fi books of the time: weak female characters. Women in Dream Park largely serve as props for male protagonists. Niven and Barnes often describe female characters by how they look, not how they function, whereas the men can be handsome and smart, brave and leaderful, or whatever else they need to be. This problem doesn’t get better as the books walk through time, perhaps reflecting some rigidity of outlook on the authors’ parts.

Despite this unfortunate byproduct of the time, Dream Park was daring for its era, incorporating concepts like NLP and sensory programming before we fully understood them. Niven and Barnes put the speculation back into speculative fiction, weaving some impressive what-ifs, even as they failed to imagine women as the equals of men.

Even with its sequels crashing and burning, the original Dream Park is still a killer read. It’s a standalone sci-fi mystery that holds up today. Just pretend the rest don’t exist.

Roll with Advantage

If Dream Park left a legacy, it’s this: strong characters playing the game, not speedrunning it. The heroes don’t break the system. They wrestle it to the mat, kicking and screaming. There’s friction between the game masters and the players, but they’re both chasing the same goal: tell a bloody good story and make it through in one piece.

Because the game’s integrated into the real world, the story has real-world stakes. You can die, like, for real. If you fail, not only does a villain get away with murder, but Dream Park’s head of security could be out of a job, the people he loves will suffer hardship both emotional and financial, and the entire industry of live-action gaming will be tarnished, perhaps sunset for good.

It’s not about min-maxing. It’s about storytelling. That’s why Dream Park still holds up. Even in 2025, nothing has quite matched what Dream Park did, because it never lost sight of the story inside the game.

Guardians of the Flame: The Sleeping Dragon, or: When We Fumble to Success

By the early ’80s, Dungeons & Dragons wasn’t just a game. It was, according to certain pearl-clutching conservatives, a direct hotline to Satan. Parents panicked, preachers frothed, and law enforcement genuinely pondered whether rolling a d20 could summon demons. This moral meltdown reached its absurd peak with the 1982 made-for-TV movie Mazes and Monsters, where a young Tom Hanks plays a college student who loses the plot after too much D&D. It was a fear-driven steel wool enema to geekdom, spicy with paranoia and seasoned with a complete lack of actual research.

Joel Rosenberg did not give a fuck.

In 1983, he dropped The Sleeping Dragon, the first book in Guardians of the Flame. People called it a portal fantasy because we didn’t know how to spell LitRPG back then, but let’s be Dr. Phil and keep it real: it does the same thing modern LitRPG does.

While Rosenberg’s tremendous brass balls and timing can’t be ignored, this wouldn’t be as good a story if the books were shit. They are not shit. I’ve read and re-read every one, and the most disappointing aspect is that there won’t be more; Rosenberg died in 2011 at a too-soon age of 57.

His wife said he came to write Guardians of the Flame after saying, “Boy I'd really love to be in the world of my game.” He woke one night and said, “This is what it would really be like.” Rosenberg, like Niven and Barnes before him, made a great series because he didn’t over-egg the pudding, or drown it in exposition gravy. His books are grounded, a love letter to the industrial revolution, complete with all the blood, sweat, and, “Oh God oh God, we forgot about sanitation,” moments that come with dragging a world into modernity.

See, in The Sleeping Dragon, a group of college students playing D&D gets transported into their game world, taking on the physical forms of their characters. Unlike Dream Park, this isn’t a simulation. While Dream Park’s real-world stakes are… real, The Sleeping Dragon takes it up a level. There’s no real world anymore. There’s no happily ever after. If our college friends die here, it’s game over, man.

The real challenge isn’t slaying dragons. It’s surviving a world where there’s no hot water, no TV, and definitely no Wi-Fi. It’s brutal, with people starving, nobles hoarding power, and a general air of medieval, “Sucks to be you.” Rosenberg doesn’t just throw his characters into the deep end; he hands them a history book and asks, “Alright, genius, how do you rebuild civilisation from scratch?” Ever tried engineering a steam engine with nothing but half a degree and sheer optimism? His novels tackle that, along with the uglier truths of history, digging up the shallow grave of slavery and shaking it for loose change.

This isn’t about skill trees and grinding XP. It’s about how civilisation actually works, and what happens when a handful of college kids try to drag a medieval world into the future.

Portal the What?

I mentioned Wikipedia calls Guardians of the Flame a portal fantasy, and it’s wrong. It’s just LitRPG before we had the term. It starts with a group of college students playing D&D and getting transported into their characters’ bodies.

If that’s not LitRPG, what is? Wikipedia needs to fix its categories immediately.

Character Sheet

Alongside the brutally realistic consequences of the stories, there’s no system to abuse. There’s no quest log, no respawning, just rawdogging adaptation and survival. It’s almost a look forward in time to games like Demon’s Souls or Elden Ring, where the world is brutal beyond compare, and you need to find out how you got there and how you fit.

This is where Rosenberg’s masterwork of characters comes into play. See, all his college gamers are real people, but the avatars the players inhabit were real, too. How much are we formed by the society we live in, versus our own moral compass? Do we want to do the right thing, or the easy one? Is morality an attribute or a privilege? Rosenberg interrogates these concepts mercilessly. The moral dilemmas lead to true stakes, because our heroes can effectively start to play god in a fantasy world.

Most modern LitRPG asks, “How do I level up?” Guardians of the Flame asks, “What kind of person do I become?”

+3 to hit

Most modern LitRPGs lean into their power fantasy. There are your store-bought god-tier protagonists breaking the system like it’s their personal playground. Guardians of the Flame doesn’t play that game. There’s no rules-lawyering the mechanics, no infinite stat exploits, just a brutal new reality where mistakes get you dead. Instead of treating the world like a min-maxing puzzle, the characters have to actually survive in it, and there’s no dungeon master to fudge the dice in their favour.

It’s gritty, but it’s also philosophical. While there are moments of power fantasy, the real heart of the story isn’t, “How do I win?” It’s, “How do we live?” There’s a real difference between a bunch of mates rolling dice in a uni common room and the same poor bastards realising they’re going to fucking die if they don’t get with the programme. No respawns, no roll-a-new-character; just five men and two women who need to get their shit together before the world gets medieval on them.

The series stays rock-solid from start to finish. No filler, no half-arsed sequels, no villainous-monologue moments. There’s no need for the usual “stop before book six” warning, because there’s not a single dud in the bunch. So instead of me telling you what to skip, I’m telling you straight: clear your schedule and read the job lot. And while Rosenberg’s death was a tragedy for both his family, friends, and fans of his work, there’s one silver lining: the final book, despite not wrapping everything up, still sticks the landing better than the last season of Game of Thrones.

If you want an RPG-inspired fantasy without plot armour and where the world’s field of fucks is barren on the matter of your survival, this is the one to read. It’s brutal, it’s clever, and unlike its inbred cousin grimdark, it actually remembers to be fun. There’s real humour threaded through the hardship, so while the stakes are high, the reading never feels like a slog. Finding a story that leaves you feeling better than when you started is practically a superpower these days.

Why These Books Are Still Awesome in 2025

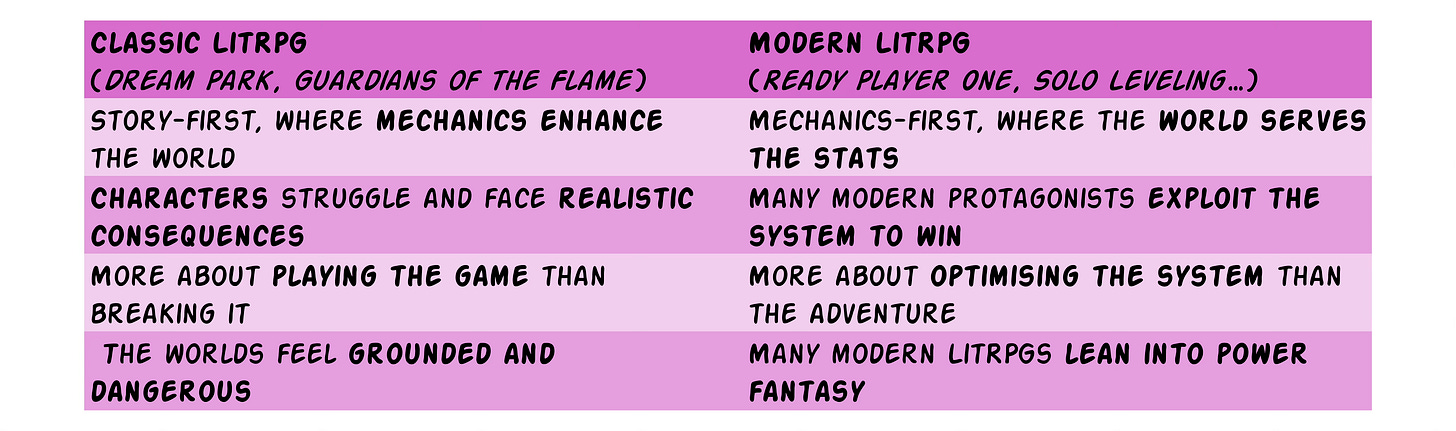

Dream Park and The Sleeping Dragon paved the way for LitRPG, but they feel different from today’s stat-heavy, more progression-focused stories.

This contrast isn’t universal. A friend who read a draft of this script demanded I include a nod to titles like Dungeon Born which manage to lean more into the origin story of the genre, proving there’s still plenty of room for nuanced storytelling. Those diamonds are out there, but if you’re here for strong characters, real consequences, and an RPG setting that has no “press X to win,” the OG LitRPG books are worth every page.

So, Should You Read These Books?

If you’re still on the fence, I’ve prepared your quick-save decision guide:

It’s a yes if you:

Love fantasy and sci-fi where the RPG mechanics serve the story, not the other way around.

Enjoy books that ask “What would you actually do?” instead of “How do I break the system?”

Want a world that feels lived-in, where failure means something more than just a respawn.

It’s a pass if you:

Prefer your LitRPGs with progress bars, skill trees, and constant level-ups.

Need a protagonist who’s overpowered by chapter three and breaking the game by chapter five.

See, Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame aren’t just early LitRPG. They’re proof the genre could have gone in a completely different direction. These books didn’t just predict LitRPG; they showed how deep it could go before the genre swerved. They set the bar with real stakes, flawed heroes, and worlds that didn’t exist just to be conquered. Surprisingly few books have picked up that torch, instead settling for the easy W of stats and progression.

For a bit of fun, I’ve included a LitRPG I wrote when I was 15. I assure you, it’s rough. It is embarrassing. And that’s why I know you won’t be able to stop yourself from cringing through it here:

[https://bf.parrydox.com/xcja1zlbxw]

Let’s talk! What’s the first game-inspired book you read? Did Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame spark your love for LitRPG, or did you come in later with Ready Player One? Drop a comment below. And if you liked this, smash that +2 Like Button of Heroism, and…

Also, I love coffee. Fund my next failed RPG character build here:

Continue this series: How to Write LitRPG Without Losing the Plot. We’ve seen what made Dream Park and Guardians of the Flame so damn compelling. But if they’re the blueprint, how do modern writers actually pull it off? Next time, I’m looking at how to craft LitRPG that doesn’t just dump stat sheets on your lap.

PS: The Rosenberg fan site is on the web archive! https://web.archive.org/web/20080527114919/http://www.slovotskys-laws.com/

Fantastic read as always Richard. Q1) Where did you get the cover for Playing the Game?

I will take your recommendation for The Sleeping Dragon, but will probably pass on Dream Park. It sounds intriguing, but I have a feeling the paper-thin female characters will ruin it for me.

I loved what you've said, I've enjoyed some of the litRPGs I've read, but some of them have been painful. (And unfortunately the paper-thin female characters don't seem to have gone away). One that was a bit different that I read recently is "He Who Fights Monsters" - it's got a comedic element that I appreciate and doesn't focus so much on the stats.

Looking forward to Part 2!

I bought both of them roughly when the came out , and before that Andre Norton had one out in 1981 Quag Keep.